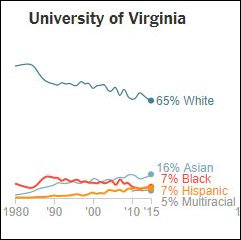

Graphic credit: New York Times. Asians and Hispanics have made large percentage enrollment gains at UVa in concert with their dramatic population growth in the state, while white percentage has fallen. Black enrollment has declined from 10% to 7%.

Even after decades of affirmative action, the New York Times has found, black and Hispanic students are more underrepresented at the nation’s top colleges and universities than they were 35 years ago.

“The share of black freshmen at elite schools is virtually unchanged since 1980. Black students are just 6 percent of freshmen but 15 percent of college-age Americans,” writes a NY Times reporting team. “More Hispanics are attending elite schools, but the increase has not kept up with the huge growth of young Hispanics in the United States, so the gap between students and the college-age population has widened.”

Blacks and Hispanics have gained ground at less selective colleges and universities but not at the highly selective institutions, the article says. Whites are slightly more “over-represented” than they were, but Asians have scored the biggest gains. In effect, Asians are displacing blacks and Hispanics.

The numbers provide quite the quandary for the New York Times. If higher education were judged by the same criteria as the private sector, one might readily conclude that the statistical disparity in racial representation reflects evidence of discrimination. Yet higher-ed, one of the most liberal-minded institutions in the country, has made a fetish of multiculturalism and diversity and has aggressively recruited blacks and Hispanics.

In seeking an explanation for the seeming contradiction between noble words and ignoble performance, the Times has stumbled upon an interesting explanation:

Experts say that persistent underrepresentation often stems from equity issues that begin earlier.

Elementary and secondary schools with large numbers of black and Hispanic students are less likely to have experienced teachers, advanced courses, high-quality instructional materials and adequate facilities, according to the United State Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights.

“There’s such a distinct disadvantage to begin with,” said David Hawkins, an executive director at the National Association for College Admission Counseling. “A cascading set of obstacles all seem to contribute to a diminished representation of minority students in highly selective colleges.”

I don’t recall such a charitable explanation ever being invoked to let private industry off the hook for racial employment gaps, which in their case are regarded as prima facie evidence racial discrimination. So, the article represents progress of a sort. But the Times still doesn’t get it quite right. To be sure, a lack of experienced teachers, advanced courses and adequate facilities may provide some of the explanation. But the phenomena of Asian over-performance and black and Hispanic under-performance applies is repeated over and over within the same school districts and even the same schools. The gap is sociological in origin.

National Review’s David French frames the issue this way:

The cohort that’s most overrepresented in American colleges and universities, Asian Americans, also happens to have the lowest percentage of nonmarital births in the United States. In fact, the greater the percentage of nonmarital births, the worse the educational outcomes. Only 16.4 percent of Asian and Pacific Islander children are born into nonmarried households. For white, Hispanic, and black Americans the percentages are 29.2, 53, and 70.6, respectively. Taken together, that means that staggering numbers of Hispanic and black children face a degree of family stress and uncertainty that their white and Asian peers simply don’t experience.

Compare children from married households, and most of the gap between Asians, Whites, blacks and Hispanics disappears. Not all of it, but most of it.

(Also part of the explanation is attitudinal differences between groups. For example, parents of Asian families are less likely to care about their children being “happy” or “popular,” or “finding themselves” than are their white socioeconomic peers. Consequently, they drive their children to excel academically. Asian-Americans tend to be more willing to defer present gratification for the future reward of attending an excellent college and pursuing a lucrative career.)

Academia has done much to perpetuate the idea that America is irredeemably racist, and that disparities in racial/ethnic representation are evidence of discrimination. I would love to hoist campus liberals on their own petard. “Hah! By your own criteria, you discriminate against minorities. You’re racist!” As tempting as it would be to take such a cheap shot, I refrain. College admissions officers can’t be held responsible for the fact that fewer black and Hispanics graduate from high school, just as high schools can’t be blamed for the fact that students from poor families and broken homes are less academically prepared by the time they reach 9th grade, and so on down the line.

The root causes of inequality are complex. It’s refreshing to see the New York Times implicitly acknowledge a piece of that reality.

(Hat tip: Reed Fawell.)