Graphic source: SCHEV

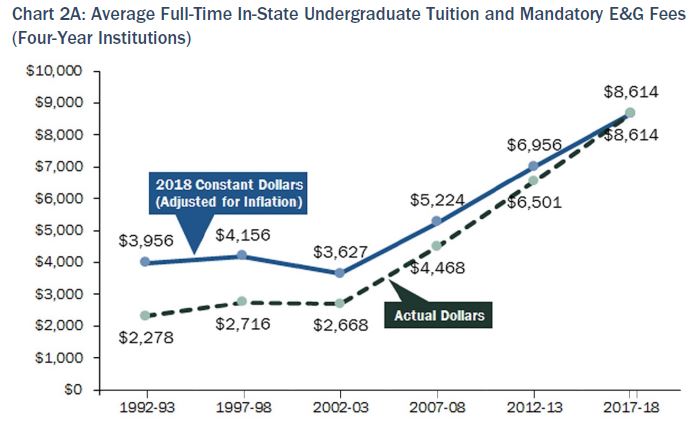

The increase in tuition and mandatory fees for in-state undergraduate students attending Virginia’s public colleges and universities will increase an average of 4.8% in the 2017-2018 academic year, according to a final report by the State Council of Higher Education for Virginia (SCHEV). That follows a 4.6% increase in 2017-17 and 6.0% in the year before.

The increase in room and board, which accounts for 45% of the cost of college attendance, will average 3.0%, finds SCHEV’s “2017-18 Tuition and Fees Report.” The total cost of attendance (tuition + fees + room + board) increased 3.9% — the lowest such increase in 16 years.

The moderating price increases suggests that “the Commonwealth’s colleges and universities are holding costs down in other areas such as student activities, housing and meals,” states a press release accompanying distribution of the report.

The SCHEV report frames the challenge of rising college tuition in the context of erratic and declining state levels of state support for higher education. States the report: “Our public system of higher education has endured eight state budget reductions in the past 10 years, and tuition for in-state undergraduate students has risen dramatically in an effort to offset these cuts. Access, affordability and quality — the cornerstones of our system — are in jeopardy.”

Says Dan Hix, SCHEV finance policy director and a lead author of the report, in the press release:

Virginia’s public institutions share our concern that college costs are getting out of reach for many. With support from the governor and the General Assembly, tuition increases last year were the lowest in many years. This year’s tuitions have gone up from that near-historic low. However, the figures show that the Commonwealth’s public institutions are working to rein in other costs.

Last year, the General Assembly and governor increased state support for higher education by more than 8%. This year, Virginia’s colleges will see an average reduction of 2.5%. This Tuition and Fees Report indicates that when the state provides additional support to public higher education, our institutions can better control the rate at which they increase tuition.

Elaborating on this theme in the report itself, SCHEV stated:

An important lesson can be learned, or a “best practice” derived from the 2012-2014 biennium. Here, Virginia made a clear reinvestment in higher education after several years of state budget reductions. In 2013 we experienced an average increase in state funding of about 5% and another 3% in 2014. With these investments came the lowest increases in tuition and fees in a decade.

Despite SCHEV’s positive spin on the numbers, the total charges for Virginia undergraduate students rose to 47.7% of their families’ average disposable income — up almost 12 percentage points from a decade ago, and considerably higher than the national average of 43% in 2016.

To develop a more sustainable, consistent level of state funding, SCHEV has been developing strategies for increasing revenue, from admitting more out-of-state students who pay higher tuition to giving elite institutions more latitude to raise tuition and redistributing the proceeds to institutions that don’t have the market power to raise charges.

“The changes would not be easy or without risk,” says the report, “but the alternative may be diminished access to a generally degraded system. If the next 10 years are similar to the last 10 years for Virginia public higher education, our system is in peril and all options to improve its future should be considered.”

Bacon’s bottom line: I’m on vacation, and I don’t have time to make a detailed analysis, but I will make a couple of observations. Over the long term (20 to 25 years) the evidence is strong that declining state support for higher education has been one of the factors contributing to steadily rising in-state costs for undergraduate students. But SCHEV frames the issue as if state support were the only factor pushing the cost of attendance higher. As a consequence, SCHEV places the onus of change entirely upon state lawmakers to cough up more taxpayer money — and none of the responsibility on colleges and universities to reconsider policies and practices that might contribute to the runaway cost of attendance.

I have blogged about some of the practices — raising more money for financial aid, hiring more administrators, declining faculty productivity, paying for star faculty, and improving student amenities — that might be contributing to the inflation in costs. Without data on all the forces at work, our understanding of tuition inflation will remain partial and inadequate.

The most important higher-ed legislation that the General Assembly could enact in the 2018 session would be to give the SCHEV the legal authority and resources to collect and analyze data that would illuminate these other factors.