Over on Cranky’s Blog, it appears that John Butcher, like me, has little better to do this Memorial Day weekend than to ruminate upon the implications of a recent New York Times op-ed piece written by columnist David Leonhardt. Lamenting the paucity of smart kids from poor schools admitted to the nation’s elite universities, Leonhardt attributes much of the decline to cuts in state support, which forces universities to raise tuition, which in turn makes makes it harder for poor kids to attend. (I previously addressed Leonhardt’s column here.)

Leonhardt believes that the decline of poor kids in elite schools represents a closing off of the nation’s meritocracy. But an alternative way of looking at the picture is that elite schools admit the smartest kids, and that the smartest kids (as defined by SAT scores, which predicts academic success in a higher-education context) tend to be found among poor households in significantly smaller numbers. There is a social problem, but it isn’t elite university admission policies. The question isn’t why elite universities are failing poor kids. It’s why K-12 systems are failing them.

In his op-ed, Leonhardt presents a chart that shows the percentage of Pell Grant students at 20 elite public universities. The University of of Virginia and Virginia Tech are second and third lowest.

Cranky responds to these data points this way: “Those low numbers are not a problem unless one thinks that these schools should dilute their brands by admitting less qualified students.”

That is a tremendously important point. Read Cranky’s post to follow his logic and view the data supporting it. In the end, he concludes that a much more interesting question than Leonhardt’s is why poor kids graduate from college at much lower rates. And that brings us to the dismal quality of academic preparation offered by many high schools, as evidence by an article in today’s Washington Post profiling a Washington, D.C., public high school, Ballou High School.

Teacher turnover in schools serving lower-income populations — 25% at Ballou this year — is a perennial scourge. At Ballou, departing teachers cited frustration with large classes of students who were far behind academically, lacked the foundation to be successful, and often disrupted class. School administrators provided little backup to enforce order. As full-time teachers dropped out, temps and substitutes filled in. Instruction became disjointed and incomplete. Even motivated students suffered.

“Students simply roam the halls because they know that there is no one present in their assigned classroom to provide them with an education,” wrote a music teacher. “Many of them have simply lost hope.”

The Post described the situation of 11th-grader Dwight Harris:

Harris said that since his teacher left, he hasn’t learned much in algebra. Substitutes have told him and his classmates to fill out worksheets, he said, which they answer by Googling the problems.

Many times, Harris said, he stays in the room for 10 minutes, long enough for the sub to mark him present. “I have no idea what my grade is right now,” he said, “but I think I’ll pass the class.”

Admittedly, Ballou is an extreme example of dysfunction, severe even by inner city standards. But problems like social promotion, disruptive students, disorderly classrooms, demoralized teachers, and excessive reliance upon temporary and substitute teachers are endemic. Students may be natively intelligent but it is a stretch to think that someone like Dwight Harris, no matter how bright and motivated, can graduate from such an environment as academically prepared as his peers at functional high schools.

Virginia high schools are graduating a higher percentage of students than ever. Consequently, a higher percentage of young Virginians, especially from poor households, are looking at college as the next step in their career progression. But are they academically prepared for college-level work? I’m persuaded that many are not.

To circle back to Cranky’s point, UVa could compromise its admission standards in order to appeal to the egalitarian sensitivities of David Leonhardt. But would that be a good idea?

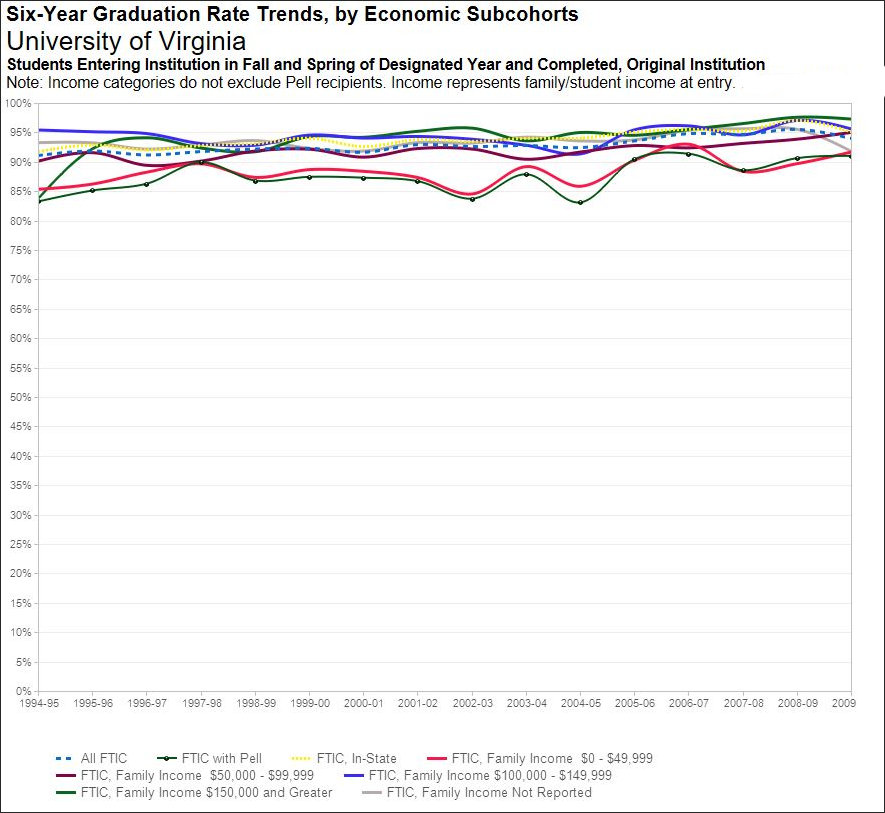

At present, lower-income kids at the University of Virginia graduate at almost the same rate as rich kids, as can be seen in the graph at the top of the post. (The gap is wider at Virginia Tech, comparable to that of Virginia four-year institutions as a whole.) In other words, poor kids who gain admission to UVa deserve to be there. They are not displacing other students who could benefit more from a UVa education.

What if UVa began relaxing standards to admit more poor students? Would the poor students wind up better off than if they had attended a different university for which they were academically prepared? Or would they drop out at higher percentages after taking out big loans and saddling themselves with debt? Even from the perspective of the poor kids — to say nothing of kids who would be displaced — it could well be counter-productive to ask UVa or other elite universities to compromise their standards.

The problems of poor kids can be traced back to high school, and from high school back to middle and elementary schools, and from there to poverty-ridden environments at home. That’s the real issue, not a lack of socioeconomic diversity at elite institutions.