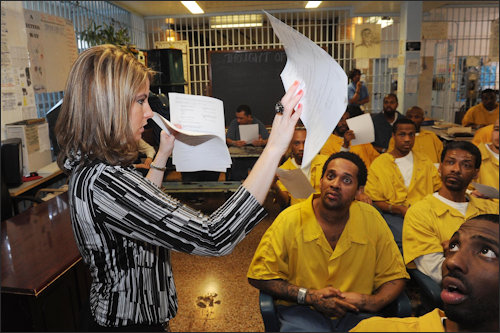

Sarah Scarbrough interacts with Richmond city jail inmates. Photo credit: Style Weekly.

Richmond Sheriff C.T. Woody spent his early career as a policeman and detective putting people behind bars. As sheriff, he has made his mark by trying to keep people out of jail.

One of the smartest things Woody did was bring on Sarah Scarbrough as director of internal programs at the city jail to deliver programs that give inmates the life skills needed to cope on the outside. One of the smartest things that Scarbrough has done is to subject the jailhouse programs to rigorous social scientific analysis to determine what works to reduce recidivism and what doesn’t.

A recent study by a University of Richmond professor, Lisa Jobe-Shields, found that inmates who enroll in the city’s Recovering from Everyday Addictive Lifestyles program have shown a demonstrably lower rate of recidivism than those who don’t. But the study had an important caveat — the results apply only to those who participate for more than 90 days, reports the Richmond Times-Dispatch.

Nationally, recidivism runs between 60% and 70%. In Richmond, where Woody has long emphasized learning and self-improvement programs in the jail, the rate is lower. The Jobe-Shields study found that the rate for inmates who participated in the Addictive Lifestyles program for more than 90 days is lower still: Only 30% re-offended within a year of release, compared to 55% who didn’t. There was no difference in the rate for those who took party for fewer than 90 days.

As the Times-Dispatch describes the program, it “treats jail life like a full-time job where male and female inmates complete classes ranging from remedial math and creative writing to anger management, parenting and drug abuse treatment through a 40-hour week.”

The study provides feedback for improving the program. Noting that the city jail is a short-term facility, some inmates don’t stay long enough to complete the program. Scarbrough said she plans to add evening and weekend sessions to extend the program beyond a 40-hour week. She also would like to provide support to inmates who were released from graduating from the program.

Bacon’s bottom line: I’m not saying that Woody and Scarbrough have devised the nation’s best anti-recidivism program — there may well be programs in other parts of the country that do just as well, or even better. But they are going about the job the right way, and results should improve over time as they incorporate feedback and make continual improvements to the program.

The sociological reality is that many jail inmates come from shattered families and dysfunctional subcultures of poverty, and had no one to teach them basic skills required to function successfully in life. In the Woody-Scarbrough paradigm, jail does far more than keep criminals off the streets — it provides an opportunity for inmate to learn life skills that will enable them to function successfully in society as workers, parents, family members and members of the community.

It is a truism that jails and prisons can be incubators of crime — inmates learn how to be more successful criminals. Likewise, it is a truism that society should invest in giving inmates the skills they need to become productive members of society. Jails offer many programs run by noble-minded people with ideas of how to help. But which skills are most needed to function on the outside? What is the best way to inculcate those skills? Which programs work the best, and what traits make them successful? Virginia sheriffs can’t reliably make those judgments based on anecdotal evidence.

Finding reliable answers requires social scientific rigor. By nudging government programs toward what works, social-scientific insights can save thousands of inmates from lives of crime — and, as a worthwhile bonus, save taxpayers millions of dollars.