This post gets a little wonkish, but hang in with me. Useful conclusions are reached by the end. The heart of the scientific method is to propose falsifiable hypotheses. You frame a hypothesis, make a prediction, and check the data to either verify or falsify the prediction. In my own clumsy, untutored way, that’s what I do when I can in the messy realm of public policy.

So, I’ve been working on a series of articles on the success, or lack of it, of higher education policy in Virginia since the enactment of the watershed 2005 Restructuring Act. I am asking whether Virginia’s system of higher education has met the goals articulated in that legislation — in particular, of primary interest to me, the goal of ensuring affordability and accessibility. What are the drivers of higher ed’s ever escalating costs?

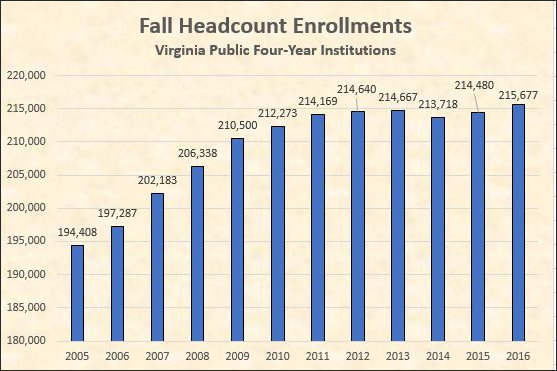

One working theory is that the expansion of Virginia’s higher-ed system to accommodate increasing enrollment might have been a significant factor. Between the fall of 2005, the year the restructuring act went into effect, and the fall of 2016, the most recent year for which we have data, enrollment at Virginia’s public four-year colleges and universities increased 10.9% — reaching 215,700 students. By necessity, growing enrollment by more than 22,000 students over 11 years — roughly the equivalent of adding a James Madison University to the system — requires hiring more faculty, erecting new classrooms and dormitories, expanding student services, and hiring new administrators, all of which adds expense to the system. Have higher-ed institutions financed the expansion in part by aggressively raising tuition?

I expected the answer to be yes. I ran the numbers. It appears that I was wrong.

This chart, based on State Council for Higher Education in Virginia data, shows how enrollments surged between 2005 and 2001, then leveled off through 2016.

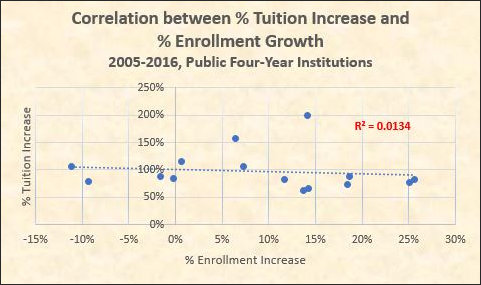

For each of Virginia’s public, four-year colleges and universities, I plotted the percentage increase in enrollment and percentage increase in annual tuition between 2005 and 2016, as can be seen in the scatter graph below.

The trend line shows virtually no correlation between the two. The R² of .0134 suggests that almost none of the variability in tuition increase over the time period is explained by enrollment increase.

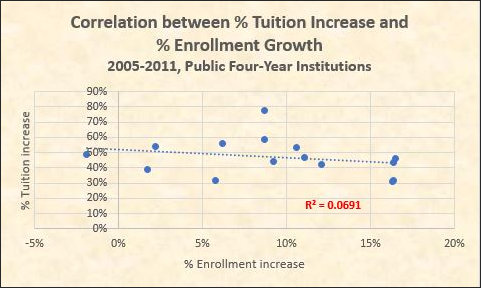

Next, I observed that almost the entire enrollment increase occurred between 2005 and 2011. Could there have been a strong correlation during that period, which was washed out by subsequent years? To see, I plotted the data for enrollment and tuition increases between 2005 and 2011.

The data shows a marginally tighter correlation, with an R² of .0691, suggesting that about 7% of the tuition increase between 2005 and 2011 can be explained by the surge in enrollment. It would be hard to make the case from this data that expanding enrollment had more than a weak, secondary effect on tuition.

If enrollment didn’t drive tuition higher, what did? We know that declining state support per student put tremendous pressure on university administrations to boost tuitions, accounting for half or more of the increase. Everyone knows this to be the case, so there’s nothing new to uncover. Of greater interest is what internal university forces have been driving tuitions higher? One likely contributor has been a push to bolster financial aid for lower-income students. Another possibility I’ll examine is the imperative among research universities to win more external research contracts. One might hypothesize that universities have raised tuition in part to build the expensive labs, hire the star faculty and recruit the promising graduate students it takes to win more contracts.

I don’t know the answer to those questions yet. But I’ll keep digging.