Here we go again… The Richmond Times-Dispatch tells us this morning that a “pattern” in Chesterfield and Henrico counties of suspending black students with disabilities at a disproportionately high rates has triggered a response from the state. Chesterfield, Henrico and the City of Richmond are among seven Virginia school districts mandated to set aside federal money under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act to address the problem.

In the 2014-2015 school year, Chesterfield was four times more likely to give a long-term suspension to an African-American student with disabilities than other students with disabilities. Despite several years of trying to reduce suspensions, Henrico was 6.7 times more likely.

In Chesterfield, an “equity coordinator” will aim to get at the “root causes” for the disparity. “It’s not that people are racist. That’s too easy,” said Julie McConnell, an attorney who runs the Children’s Defense Clinic at the University of Richmond. The bias, she said, is subtler. “If a child doesn’t act like your child, it’s harder for people to understand.”

The implication here is that the pattern of disciplinary action is discriminatory in effect, if not in motivation. Accordingly, offending jurisdictions like Henrico and Chesterfield are singled out for revamping their disciplinary policies. The new thrust, as described by T-D reporter Vanessa Remmers, is to discipline students “in a nonpunitive way, by focusing on repairing harm done and engaging everyone involved rather than excluding the misbehaving child.” Thus, schools become an agent of let’s-all-hold-hands-and-sing-kumbaya social welfare policy.

The article does not tell us how many children are being suspended, much less how many handicapped black children are being suspended, as justification for overhauling district-wide disciplinary programs. The article does not tell us whether the suspensions are commensurate with the number of number and severity offenses. The article does not tell us the number of victims, either students or faculty, of misbehaving students. The article does not tell us what impact poor school discipline has on the learning environment for other students, much less how black students might be adversely affected by disrupted classrooms.

In other words, the article frames the social problem as one of bias and discrimination against black children with disabilities without regard to the impact their behavior has on anyone else, such as black children who do not create trouble at school. Indeed, by ignoring the disproportionate impact of the supposed remedies upon the educational environment of four-fifths of African-American students, one could say that the undue focus on bad actors is itself a form of bias and discrimination.

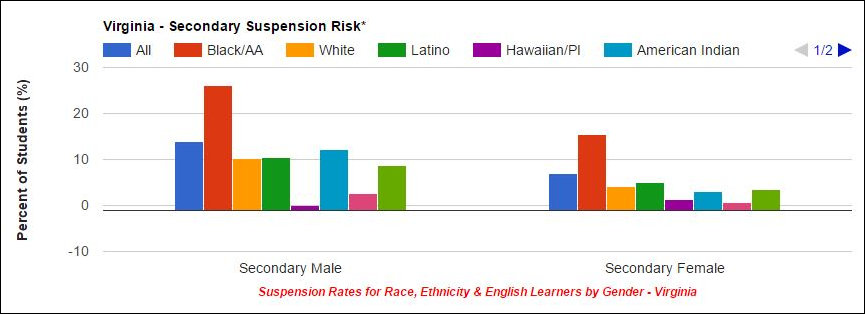

Here is a quick look at some statistics that might present the issue in a different light. This data comes from the Center for Civil Rights Remedies:

In Virginia secondary schools in the 2011-2012 school year, males were disciplined at roughly twice the rate of females. By the logic of the Children’s Defense Clinic, the ACLU, the Obama administration and other advocates of “disparate impact” theory, the school system discriminates against males. This would seem incontestable. But no one raises this issue. No one seems remotely concerned.

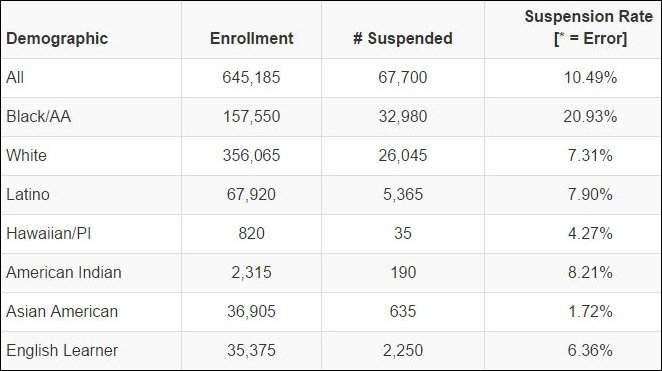

Here’s the data for the suspension rate broken down by ethnic/racial/linguist groups for 2011-2012:

Here we learn that the disciplinary rate for African-Americans in secondary schools is three times that of whites — but that the disciplinary rate for whites is roughly the same as it is for Latinos and American Indians, higher than the rate for English learners, and more than four times the rate for Asians. Perhaps the most accurate way of presenting the data is to say that prevailing practices have a disparate impact on non-Asians!

Here is another way to frame this data: While 21% of African-American students were suspended in 2011-2012, 79% were not! These students did not create major disciplinary issues. But they had to suffer through the disruptions inflicted by their unruly peers. Again, social justice advocates never mention this.

Here’s another set of data, this from the 2014-2015 Virginia Department of Education “Discipline, Crime and Violence Annual Report.”

The incidents highlighted at left are only the most severe. They do not include 22,388 incidents of defiance of authority/ insubordination, 17,450 incident of classroom or campus disruption, 15,894 disruptive demonstrations, 12,523 minor physical altercations or countless other offenses adding up to 145,413 in all. These numbers also do not include acts of indiscipline too routine to even bother reporting in a system where deviancy is continually defined down.

No one tracks the race/ethnicity/linguistic background of these victims.

Here are other data sets for which there is no data because no one collects it:

- Number of classes disrupted.

- Number of teaching hours disrupted.

- Number of student learning hours disrupted.

- Academic cost to students of lost learning hours.

Yes, school systems need to take into account the fact that many students come from extremely challenging home environments, and many may suffer from disabilities that make it difficult for them to plug into the normal school environment. We should feel compassion for these kids, and perhaps we should make special arrangements for them. Perhaps it’s time we question the commitment to mainstream them with other students. In the meantime, we should stop assuming that disparate impact equals discrimination, and we should stop contort school disciplinary policies to meet the needs of the few rather than the needs of the many.